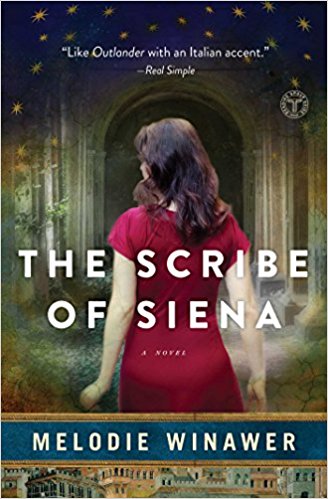

by Melodie Winawer

The ancient beauty of the Palio can not be duplicated

Full disclosure: I am not from Siena. I am not even Italian, though, like many Americans, I wish I were, and all three of my children have Italian names—one so intensely Italian only Italians can pronounce it properly. (Poor girl, spending years having her name mangled by friends… but she loves it anyway).

Despite my origins, I decided, seven years ago, to write a historical novel set in Siena. The Scribe of Siena, which was published in May of 2017, is a tribute to that extraordinary city—its history, its traditions, and its singular magic. Since the book came out, I’ve been asked many terrific questions: how I learned about medieval Italian cuisine; why I, a neurologist and neuroscientist, decided to write medieval Italian historical fiction; and whether the book is autobiographical. (Answer: no, and yes, like all novels.) But one of the most common questions I get asked during readings and interviews is “Why Siena?”

The answer to that question is not only a description of one particular writer’s motivation, but a sort of travel guide too—one that I hope might make you want to go to Siena if you haven’t already, and return if you have. Maybe it will even inspire you to travel there virtually, through reading.

It may seem like a non sequitur, but in order to explain what is so remarkable about Siena, I’m going to talk about the Queen of England. In January of 2016, Queen Elizabeth was three months from her 90th birthday, and party planners were busy putting together a huge celebration for the celebrated monarch. The Queen is well known to be a great lover of horses, and with that in mind, the organizers decided that the ideal tribute to Her Majesty would be to bring Siena’s Palio to London. They hoped to transport the world-renowned horserace, which has occurred twice a year for hundreds of years in Siena, miles from its home. The Palio is one of Siena’s most powerful traditions—two annual races in which horses representing the medieval districts of Siena, the contrade, vie for the win in the Piazza del Campo. The races coincide with important religious holidays. First, on July 2nd—The Palio di Provenzano – in honor of both the feast of the Visitation and a local festival celebrating the apparition of the Virgin) and then August 16—The Palio Dell’Assunto – marking the feast of the Assumption.

The Palio is not only a thrilling spectacle—three terrifying laps around the tight turns of the Campo, filled with earth (La Terra in Piazza) for the purpose – but also a passionate representation of centuries-old contrada pride, and fierce rivalry. In the 75 to 90 seconds it takes for the horses to run, much more than the symbolic prize Palio banner of the Virgin Mary is at stake.

When party organizers invited the Palio to England for the Queen’s celebration, they had a nasty surprise: Siena refused, despite the fact that the request came on behalf of the ruler of the British Empire. International newspapers reported the shocking news, complete with provocative headlines such as “Siena Palio snubs British Queen’s birthday invite” accompanied by photographs of the Queen, dressed in her habitual lovely blue.

A spokesperson for the Magistrate of the Contrade, the group that organizes the race explained: “The theatre of the Palio is the Piazza. Outside of that space it doesn’t make any sense.”

That brief explanation—which was more lesson than apology – holds an important key to understanding Siena, and is at the heart of why I wrote a novel about this extraordinary city.

There are many cities in Italy (and all over the world) in which evidence of the past remains vivid: in the centuries-old buildings, the cobbled streets, piazzas where markets once filled with the bustle of daily life, and where tourists now wander with open mouths, taking in the sights. But in Siena the past is more than a memory—it lives and breathes, part of the essential fabric of daily life. Siena’s residents still claim allegiance to their contrade, baptizing children in each district’s font, proudly wearing the scarves displaying medieval symbols and colors—orange and white for Leocorno, the Unicorn; blue and yellow for Tartuca, the Tortoise; red, white and black for Civetta, the Little Owl; and the fourteen other wards remaining from Siena’s medieval past.

When I was last in Siena, I left my three children doing somersaults down the sloping Piazza del Campo (with another responsible adult, of course) and within moments of walking into a side street heard the sound of drums. I followed the sound that echoed through the narrow alleyways until I found myself, magically, in a tiny courtyard, the seat of the Civetta contrada, where two boys solemnly practiced the complex ritual with the huge banners that they would someday carry through Siena’s streets. Another boy played the hypnotic rhythms on drums that would accompany the Palio parade through the city and into the Campo packed with earth and filled with thousands of people. They practiced intently, watched and guided by their elders. The few other people who found themselves privy to the practice session watched silently too. Within seconds of turning the corner from a plaza filled with postcard shops and cafes, I’d walked straight into another century.

This is why Siena’s Palio couldn’t possibly come to London, even for the Queen’s birthday. Siena’s traditions are not shows, not tourist amusements, not reenactments. They are seamlessly woven into daily modern life. The Palio could no more be moved to England than Siena itself.

In The Scribe of Siena, my protagonist Beatrice, a modern New York neurosurgeon who inherits both her late brother’s Siena home, and his research into Siena’s devastation by the 14th century Plague, becomes increasingly absorbed in the history and mystery her brother was investigating. Entranced by the writings of a 14th century fresco painter Gabriele Accorsi, and the singular way in which Siena blurs the boundaries between past and present, Beatrice finds herself transported to 1347 Siena, in the midst of the dangerous conspiracy her brother was investigating, just ten months before the arrival of the Black Death.

I set the book in Siena because I love the city and its history, and could imagine spending years thinking and writing about it. But it was more than love. Siena is simultaneously modern and medieval, a city where the past and present coexist. It was the perfect place for me to set this story of a woman who, at first against her will, and then by desire, loses her place in time.

Bruno Valentini, Siena’s mayor, replied, when the Queen’s birthday request was broached: “If you want to see the Palio and really understand it, you have to come to Siena. You’ll never see a standard bearer or a drummer outside Siena. They are not circus jugglers but representatives of the contrade who tell a centuries-long history. It is not possible, I’m sorry”. (Read more)

If you want to see the Palio in person, you’ll have to visit Siena. Even if you are the Queen of England.

by Melodie Winawer

by Melodie Winawer

Melodie Winawer is a physician-scientist and Associate Professor of Neurology at Columbia University. A graduate of Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Columbia University with degrees in biological psychology, medicine, and epidemiology, she has published over fifty nonfiction articles and book chapters. She is fluent in Spanish and French, literate in Latin, and has a passable knowledge of Italian. Dr. Winawer lives with her spouse and their three young children in Brooklyn, New York. The Scribe of Siena is her first novel.

Visit her website: http://melodiewinawer.com

Simon and Schuster author page

You can also purchase The Scribe of Siena from our Italia Living Amazon page